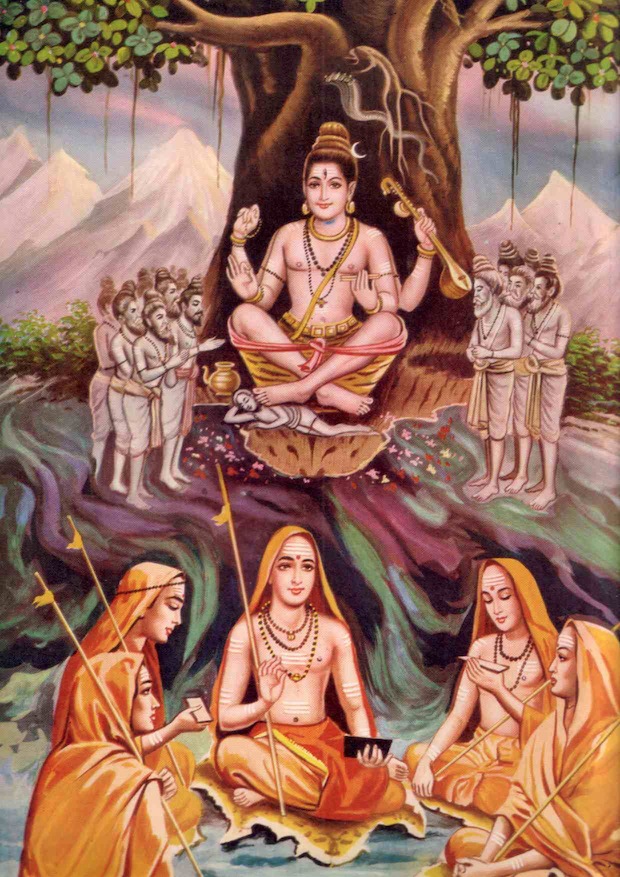

The Defeat of the Householder by the Sannyasin

Because of a series of weird coincidences and historical trends the teaching of meditation is heavily biased towards the needs of monks. This is odd because in the modern world, at least in my world, the most intense and sincere practitioners of meditation are householders.

Shankara was a brilliant and impish, irrepressible spiritual genius who lived somewhere around 788–820 AD. He was a vigorous debater, in a hurry to defeat the Buddhists and the ritualists.

The debate between Shankara and Mandara Mishra AND his wife Bharati

from Baba Rampuri’s website:

When he wasn’t composing his great texts and commentaries or establishing the four great monasteries, maths, in the four corners of India, or rediscovering countless sacred groves and shrines, he debated his way through India, overwhelming his opponents with the authority of fire, and thus revived the eternal Sanatan Dharma, the Way. His defeated foes became his disciples and the number of his followers grew with every step.

Adi Shankara faced one final test before his Victory of the Four Directions could be proclaimed to the three worlds. He had to win a debate with Madana Mishra, and it was said that the gods themselves would come to hear Madana Mishra and even they would learn a thing or two. He was revered as the most learned man in India.

When Adi Shankara arrived, he agreed, as his unsuccessful predecessors had done, that the confrontation would take place suspended in the air, three feet above the ground. After all, one had to have qualifications. Mishra’s wife, Bharati, presided over the debate, but surrendered authority to two garlands of marigolds. At the end, the man wearing the garland that was still as fresh as the day the flowers were picked, would be declared the winner.

After eighteen days of heated debate during which the open air theater of the sky was filled with all the celestial beings, the garland around Madana Mishra’s neck wilted and dried out, and Bharati had no choice but to declare her husband’s defeat. However, she refused to declare Adi Shankara the winner, as his victory was, as yet, incomplete. She reasoned that since she was her husband’s partner in all things including his learning, Adi Shankara, even though he might be the master of all knowledge, had to defeat her also.

Adi Shankara reluctantly agreed. Bharati chose the art and knowledge of lovemaking as the final subject of debate, which was a very clever choice as Shankara was a life-long celibate and had never experienced sex. Lovemaking was one of the sixty-four traditional branches of learning and Bharati asked him to explain the various forms and expressions of love, the nature of sexual love and its various locations in the body, the effect of the different phases of the moon on lovemaking, and how a man or woman may seduce the other. Perhaps for the first time in his life, Shankara admitted that he was unprepared and asked for thirty days in which to acquire the knowledge. This was a reasonable request and Bharati accepted.

Shankara knew that he would have to enter the body of another in order to acquire this knowledge, for knowledge was invalid without its experience. His disciples fanned out over the countryside and beyond searching for a candidate until they came upon a king on a hunting expedition who suffered a heart attack and died. This king, as kings were wont to do in those days, had over a hundred wives back at the palace, none of whom yet knew of their sire’s demise. Shankara and his disciples found a hidden cave for Shankara to perform his kaya-pravesh, entering of another’s body, which he had learned how to do in his youth. He went into deep meditation, and one by one shut down all of his bodily functions until he, too, was no more than a corpse. Two disciples sat in the cave and protected the vulnerable body of their master, while he did his “work,” for he would need to return to his own body later. He had explained to them that his vow of celibacy would remain intact because only the body acquires karma and the spirit remains a witness.

A short time later, to the great surprise and joy of his royal entourage, the king opened his eyes and sat up. “Must have been only unconscious,” thought his ministers and others in the hunting party as they returned to the palace. The resurrected king attended his wives, the queens, with such tenderness and passion that he was mistaken for the god of love himself. The king’s body certainly knew what to do, but Shankara’s spirit took it to new depths of experience and knowledge. So quick was Shankara’s grasp of the art and knowledge of love that within three days of practice, he was able to compose a treatise on love that he named after the king.

His ministers suspected something. The harvest was extraordinary, the trees were heavy with fruit, cows doubled and tripled their production of milk, and peace and prosperity reigned in the kingdom as never before. They suspected that the king had indeed died, and some baba had entered the king’s dead body. Body-entering was not uncommon and the ministers wanted to take no chances on the yogi returning to his own body, thus deserting the kingdom, so they sent soldiers out to look for the lifeless body of an ascetic, and they found Shankara’s body.

Fortunately, Shankara’s thirty days was just about to expire, and he managed, by a reversal of his yogic power of kaya pravesh, to make it back into his own body as the soldiers began to cremate it. As the flames were about to rise, Adi Shankara jumped out of the funeral pyre, sustaining only a burn on his right hand, and thus saving his own body. When Shankara and his disciples retuned to Madana Mishra’s place, Bharati conceded defeat before a word was uttered. She had already read the outcome in the stars. Madana Mishra gave away all his wealth to the poor and became a sannyasi, the disciple of Adi Shankara.